Our lab seeks to advance regenerative medicine by building next-generation models of human colon development and disease. Using induced pluripotent stem cells, we generate self-organizing “mini-colons” that capture the epithelial, mesenchymal, and immune complexity of the human gut, enabling precise modeling of tissue regeneration, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), and colorectal cancer in a dish.

Our lab studies how the human hindgut develops and how diseases of the colon arise by creating miniature, lab-grown versions of human organs called organoids. These organoids are made from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—cells reprogrammed from a small sample of a patient’s skin or blood that can develop into nearly any cell type in the human body. This technology allows us to model human development and disease using cells that carry the patient’s own genetic makeup, enabling powerful “disease-in-a-dish” studies.

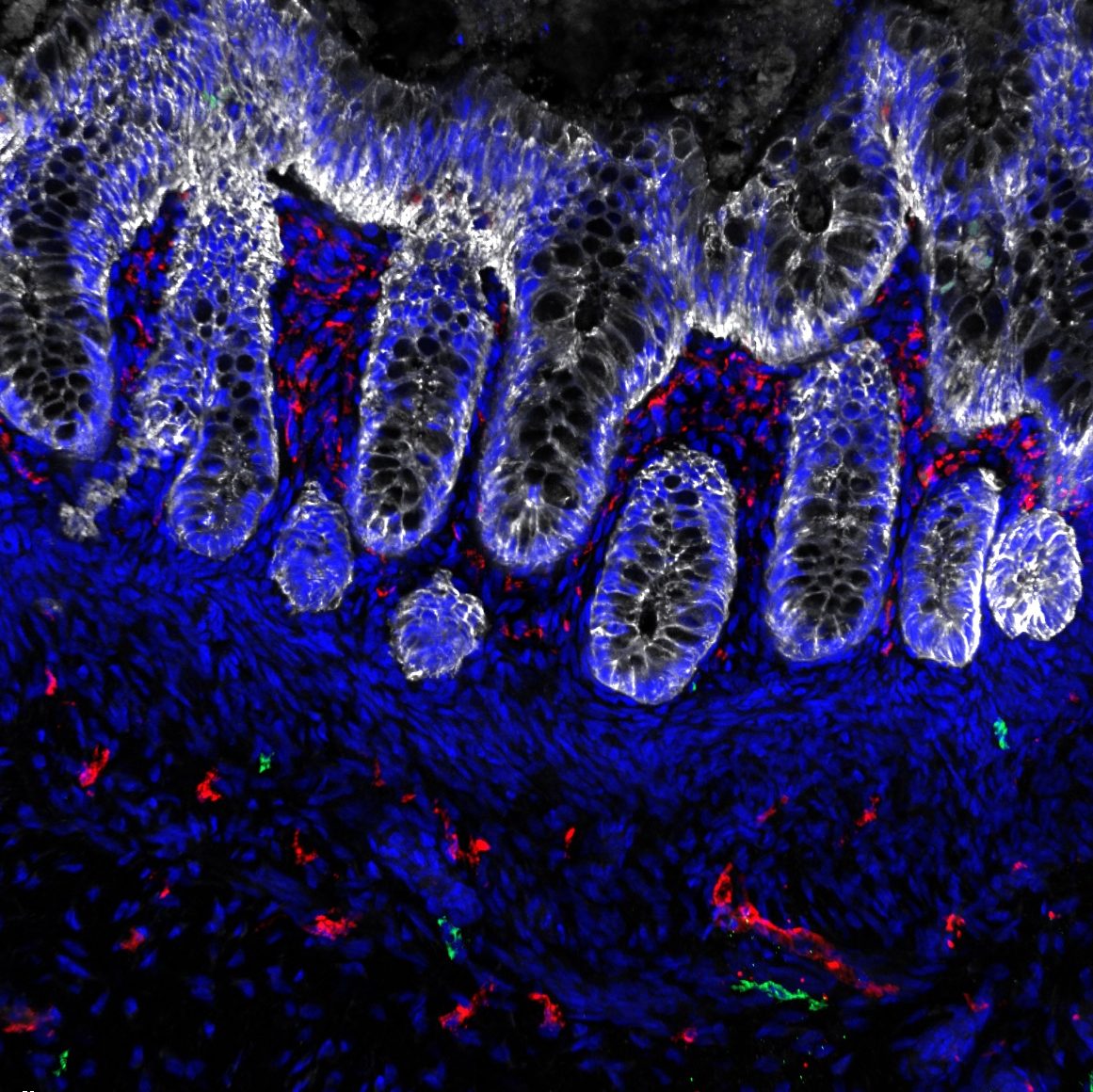

We have developed several organoid systems that model different regions of the human hindgut. These include human colonic organoids (HCOs) that contain both the epithelial lining and co-developing mesenchyme (Munera et al., Cell Stem Cell 2017), HCOs with immune progenitors that give rise to functional macrophages capable of responding to bacteria and mediating inflammation (Munera et al., Cell Stem Cell 2023), and human urothelial organoids that model the bladder lining (Qu et al., iScience 2025). Because macrophages can both protect tissues by engulfing bacteria and promote inflammation, these immune-competent organoids provide a valuable platform for studying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and related inflammatory processes.

Unlike traditional organoids composed solely of epithelial cells, our models include supporting mesenchymal and immune lineages, creating a more physiologically complete system that captures the complex cell–cell interactions of the colon. Using these systems, we aim to better understand how the gut develops and how those developmental programs are disrupted in disease.

Currently, we are using these models to study patients with mutations in the gene SATB2 and to understand how these mutations disrupt the development of enteroendocrine cells, specialized cells in the colon that help regulate appetite and bowel movements. In the future, we aim to extend this approach to investigate genetic variants associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), reconstruct the colorectal tumor microenvironment, and model developmental disorders such as juvenile polyposis syndrome, using organoid-based systems that faithfully reproduce human disease in a dish.